As a little-understood plague decimated the gay community, San Antonio-born artist Donald Moffett had a life-changing experience when he heard about Larry Kramer’s call to action in March 1987 at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center in New York, the founding moment for the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, best known as ACT UP. Moffett joined the protest group’s agitation and propaganda offshoot, the artist collective Gran Fury, which disseminated information about the urgency of the AIDS epidemic through bold graphic design and early guerilla marketing long before the advent of social media.

“There was a lot of fear and panic at the time, especially in New York and San Francisco,” Moffett told Out In SA during a phone interview from his New York studio. “Gran Fury provided the visual speech for the gay rights movement. We were somewhat independent of ACT UP. I just played a small role in a big phenomenon. But the accomplishments of ACT UP are undeniable. It really changed the dynamics between patients and doctors and the Food and Drug Administration. ACT UP helped get drugs into bodies. There was a huge bottleneck at the FDA that made it impossible for people to get the drugs they needed. ACT UP changed all that.”

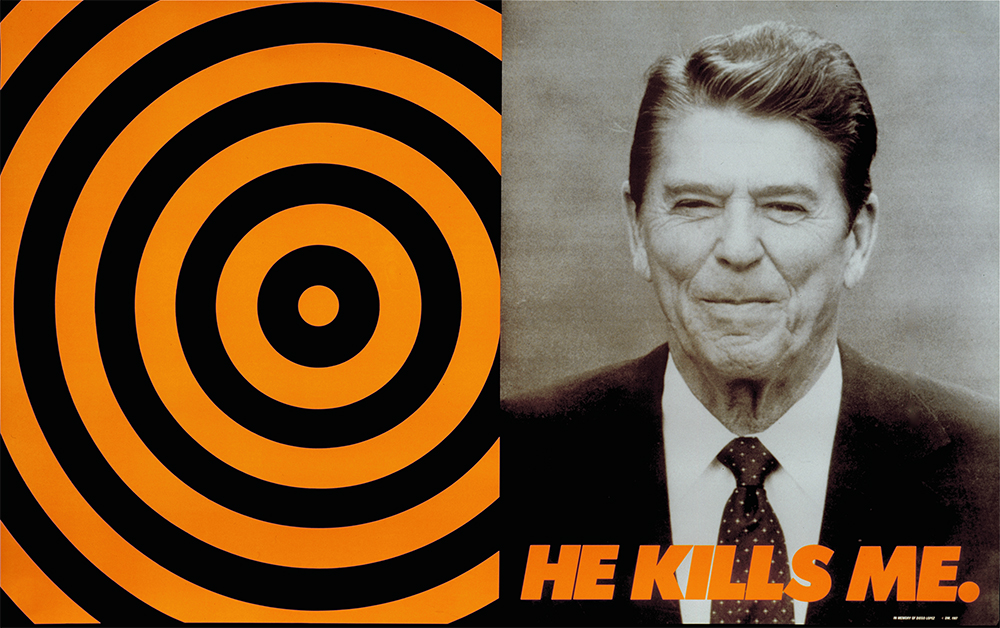

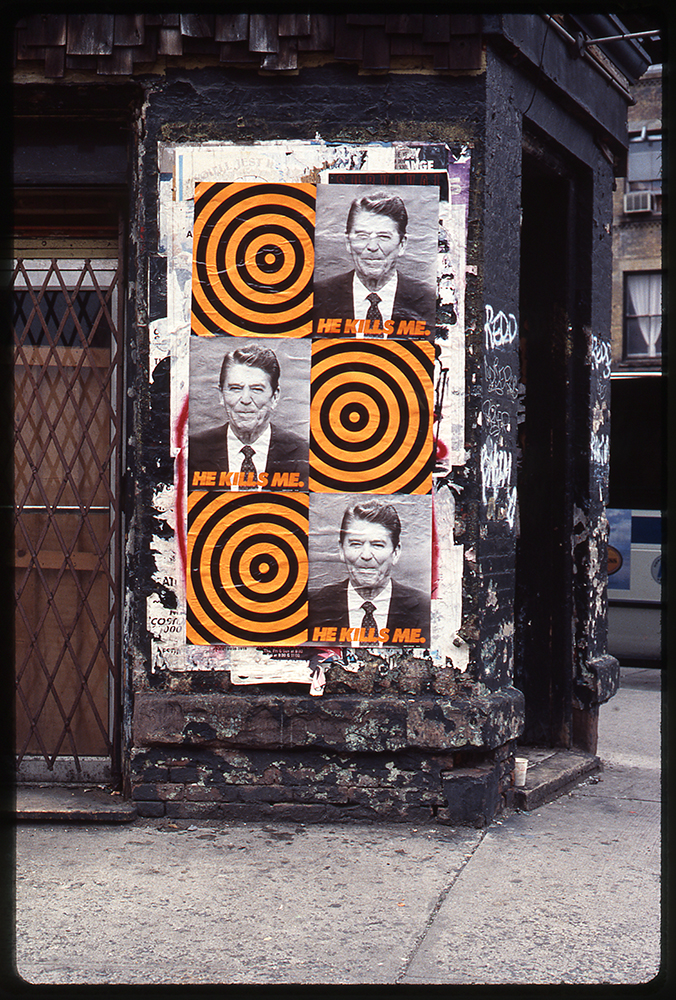

One of Moffett’s major contributions to the effort was his 1987 AIDS protest poster, He Kills Me, which juxtaposed a black-and-white lithographic image of President Ronald Reagan with a black-and-orange bull’s-eye. Last summer, He Kills Me received renewed national attention when it appeared as part of a large-scale installation in the new Whitney Museum of American Art.

Installation view of “America is Hard to See” (Whitney Museum of American Art, 2015). (Wallpaper) Donald Moffett, He Kills Me, 1987; Barbara Kruger, Untitled (We Don’t Need Another Hero, 1987. Photo by Ronald Amstutz.

“I designed it before I joined, but I gave the poster to ACT UP to use,” Moffett said. “At that time, people didn’t really know what was going on. We all felt that we had to do something, but we didn’t know what to do. There was a feeling of desperation and rage. My poster was just one of the things that started popping up on the street. I think it shows how I’ve tried to combine politics with more formal issues.”

Working with a variety of styles and media, he’s explored various strategies for extending the two-dimensional frame of a painting such as projecting videos onto the surface, peeling back the canvas to paint on the wall and building up the paint to create thick textures. Balancing social and formal concerns, his work combines the haunting social critiques of the Spanish romantic painter Francisco Goya with the tonal subtlety of the Italian painter Giorgio Morandi. Recently, he shared a booth with the influential abstract painter Frank Stella at the Frieze Art Fair in London sponsored by his New York gallery, Marianne Boesky.

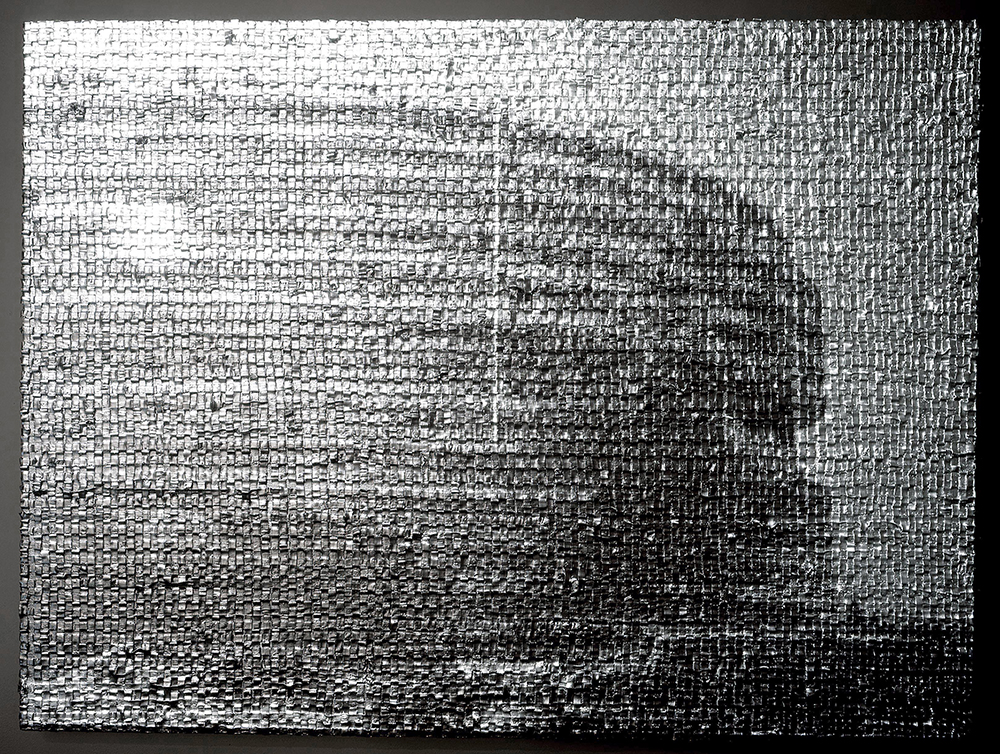

While his political activism has sometimes overshadowed his art, Moffett’s reputation is on the rise, especially in Texas. Currently, Austin’s Blanton Museum of Art is presenting a two-part installation of newly acquired works by Moffett, who touted the city in the August issue of Condé Nast Traveler. Houston’s Contemporary Arts Museum organized a major touring exhibit, “Donald Moffett: The Extravagant Vein,” in 2011. Two of his works, a video projection of the Watergate Hotel (above) and a fuzzy abstract landscape (below), belong to San Antonio’s Linda Pace Foundation.

“Linda Pace absolutely changed the whole landscape for contemporary art in San Antonio by bringing in so many well-known national and international artists to Artpace,” Moffett said.

Born in 1955 in San Antonio, Moffett attended the University of Texas at Austin for two years and then earned a BA in art and biology from Trinity University before striking out for New York City in 1978. He may have left for the Big Apple as soon as he could, but he doesn’t bear any animosity toward his hometown.

“I liked San Antonio then and I like it now,” Moffett said. “I was always involved in the arts because I had pretty supportive parents. But I grew up in the pre-Stonewall era, so for a young kid in San Antonio, being gay was kind of unknown territory. There weren’t any role models like there are now. I knew I was gay by the time I was 10 or 12, but I didn’t come out until I was much older. In fact, it really wasn’t until I went to UT. There I joined a fraternity, which turned out to be a big mistake. So when I finally came out, I pulled out of UT and went back to San Antonio where I could have a smaller, more private experience.”

By the early 1970s, Gay Pride began to be expressed more openly in San Antonio. Moffett recalls going to the clubs on Main Avenue. “There were places to go, people to talk to and sex to be had,” Moffett said. But he had set his sights on New York when he was a junior in high school and attended a special summer program at Cornell University. “I made friends with students who came up from New York, and I knew that was where I wanted to be,” he said. As soon as he arrived in New York in 1978, he headed for Christopher Street.

“Roughly speaking, I’ve always liked the outsider status of being queer.”

“It was exciting because there was so much to see,” Moffett said. “But I was 23 years old and wasn’t sure what I was going to do, although I did have an idea for a job.” While working for the San Antonio Symphony in the mid-1970s, he got to know manager Joyce Moffett, who went on to work for the American Ballet Theater.

“I figured she would help me since we shared a last name, though we weren’t related,” he said. “She didn’t have anything, but she told me to go to the New York State Theater (renamed the David H. Koch Theater in 2008) in Lincoln Center, the home of the New York City Ballet. Sure enough, they had a little job for me working as a clerk handling subscription tickets, and that’s how I got my start in New York. In the days before computers everything had to be done by hand. At first, I lived at the Vanderbilt YMCA, but I was able to move into a midtown loft when they were cheap. Breaking in as an artist was a very slow process that took years and years. I had various jobs filling in and around the edges, but I wasn’t able to make a living as an artist until the late-1980s.”

In 1989, with artist Marlene McCarty, a Gran Fury member, he co-founded Bureau, a design company that also supported their social causes. When Gran Fury disbanded in 1993, Moffett took a break from making art; but he returned in 1995, producing modestly sized abstract paintings, launching the most innovative and productive phase of his career.

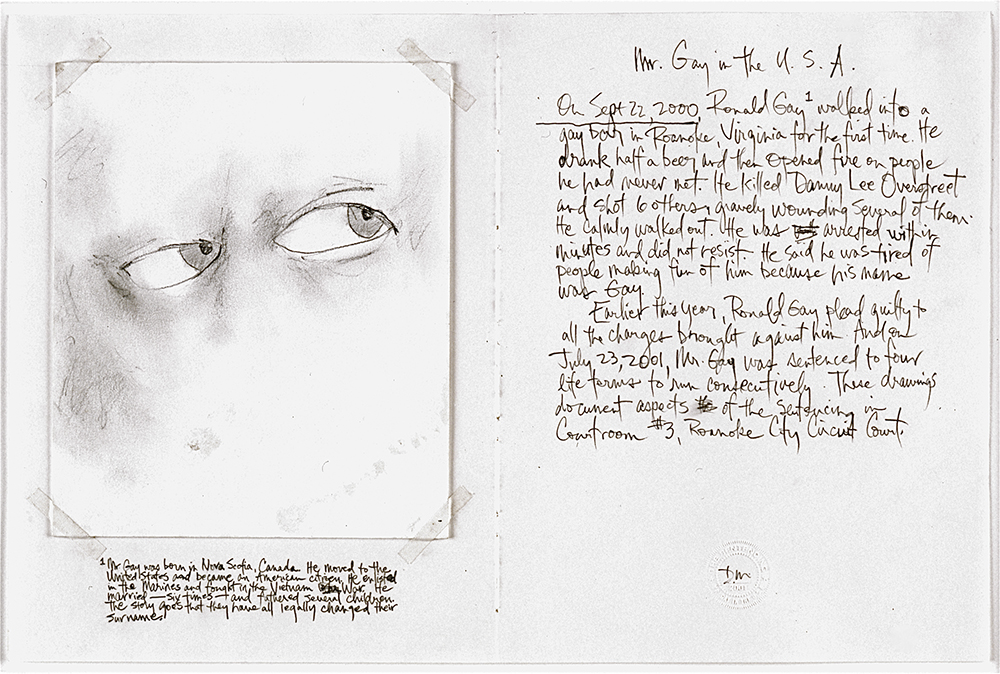

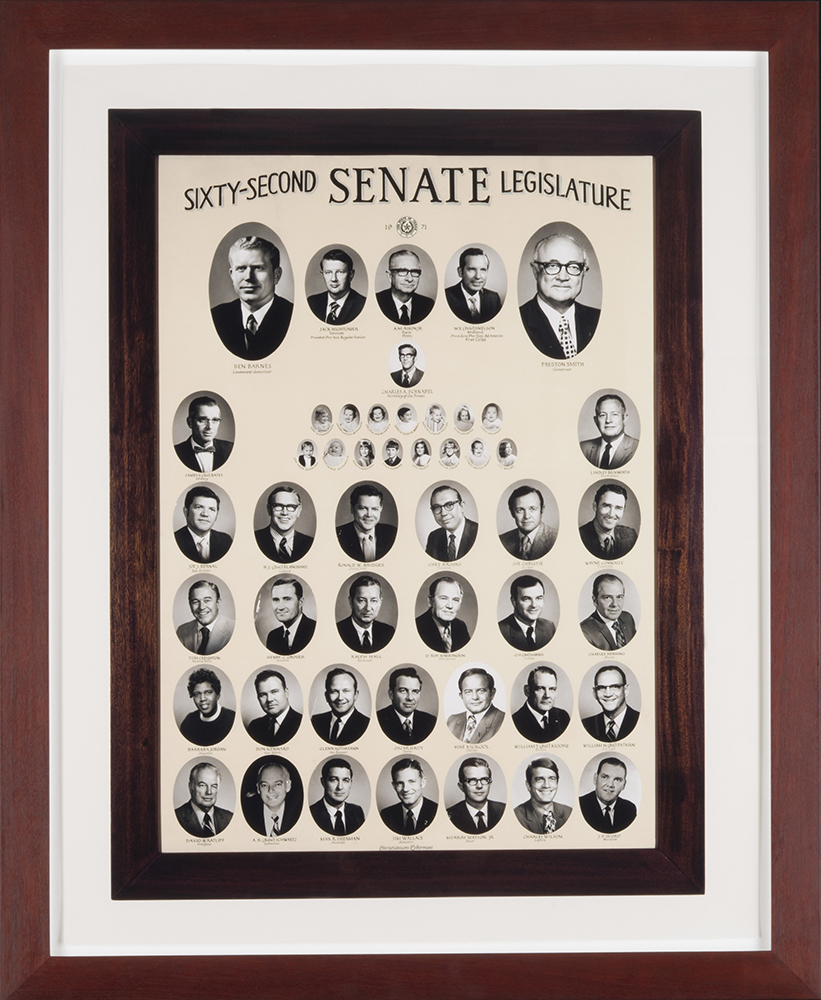

At the Blanton, the first of Moffett’s two-part installation featured 18 drawings from his Mr. Gay in the U.S.A. series, depicting the sentencing of Ronald Gay, a Vietnam War veteran who shot several people in 2000 at a gay bar in Roanoke, Virginia.

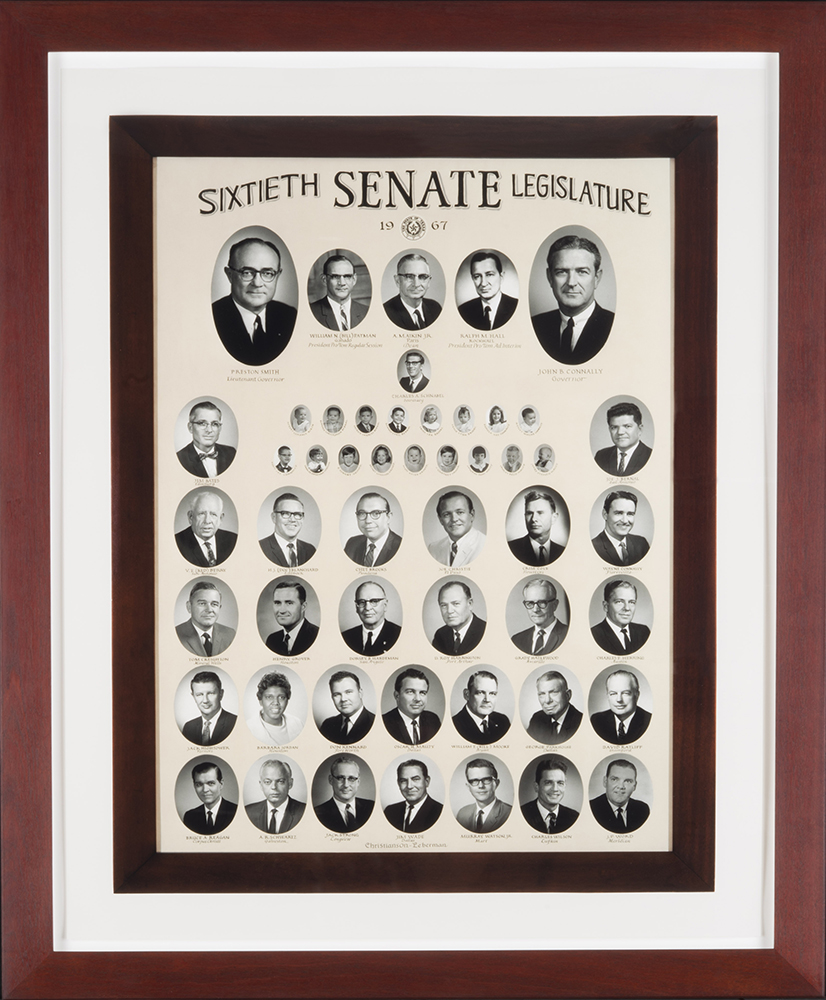

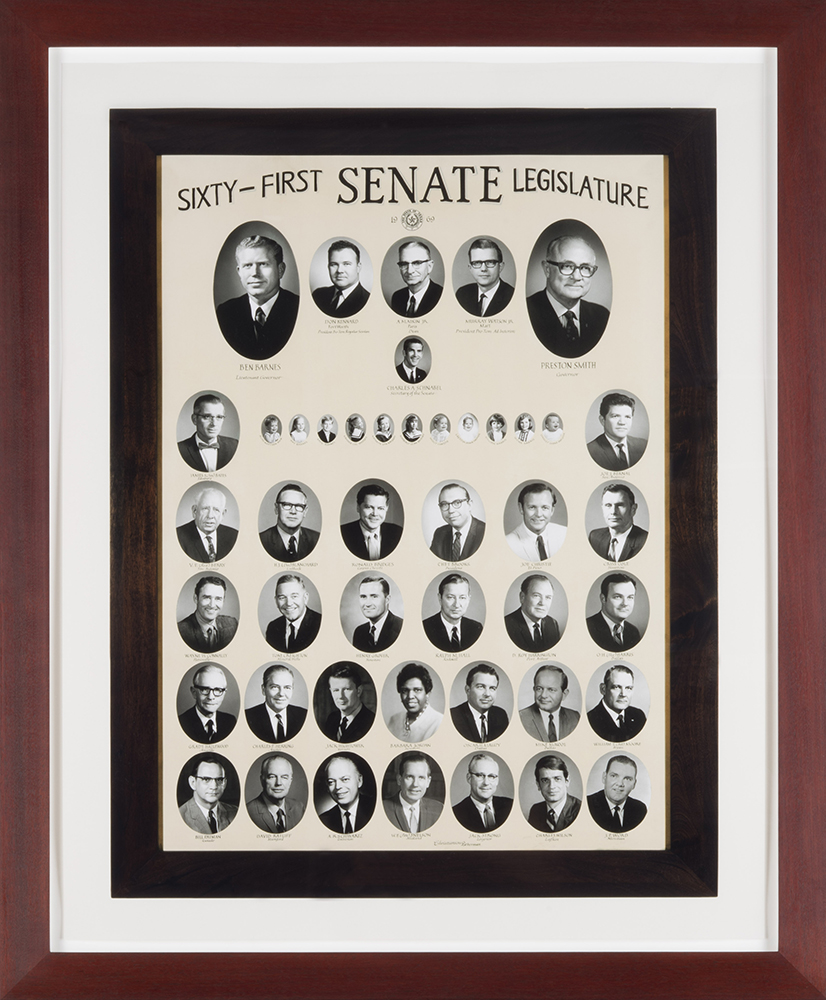

The second part, on view through February 28, includes What Barbara Jordan Wore (2001), a series of digital prints exploring the legacy of the Texas congresswoman. She is the only African-American woman wearing a dress among the rows of white men.

“Barbara Jordan absolutely was a hero to me while I was growing up in Texas,” Moffett said. “I vividly remember watching her on TV during the Watergate hearings. She’s always been an inspiration for me.”

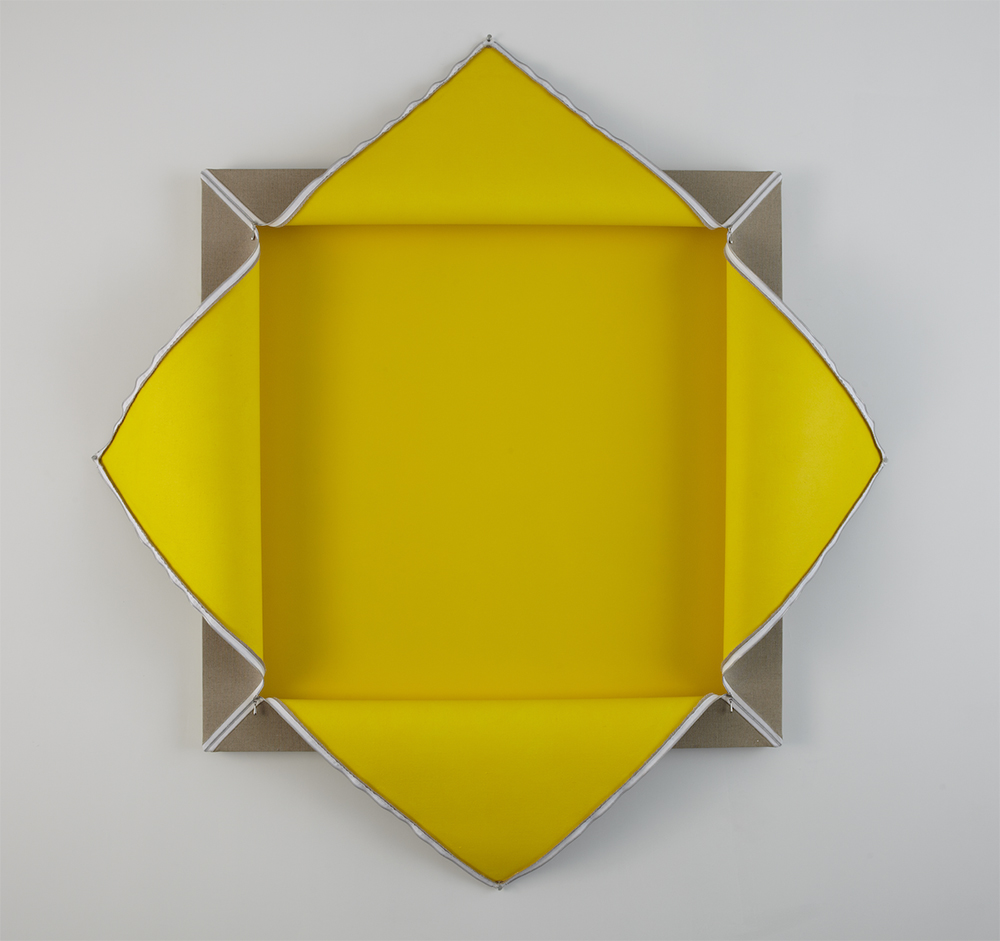

An abstract painting, Lot 102807 (Yellow) (2007), features an “unzipped” canvas that reveals, on close examination, that the central primary color is actually painted on the wall. Perhaps Moffett’s most innovative experiments have been with projecting videos on painted canvases. His Untitled/Green Roller (Lot 080104) (2004) initially appears to be an abstract blue-and-green landscape punctured by a black hole. In a conceptual, comic twist, Moffett projects a video on the canvas so a two-dimensional hand emerges from the hole and begins painting.

Lot 102807X (Yellow), 2007, acrylic polyvinyl acetate on linen and wall, with rayon and steel zipper

After his years of activism, Moffett is sanguine about the mainstream acceptance of same-sex unions. He wonders if being gay is losing some of its mystique. “Now gays are just like anybody. Roughly speaking, I’ve always liked the outsider status of being queer,” he said. “Looking at the world from that viewpoint can be immensely valuable to an artist.”

Donald Moffett

$5-$9

Blanton Museum of Art

200 E. Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., Austin

(512) 471-7324, blantonmuseum.org

On view through February 28