Ask your doctor if political art is right for you.

May cause hindsight, nausea, projectile vomiting, heart palpitations, sweaty palms, bowel irregularity, dry mouth, high blood pressure, blurred vision, violent laughter, and other uncontrollable irritations. But relax it is only art.

With your host, Gene Elder

It is impossible to ignore politics, especially now, and it will be until the vote is counted in November. And our good friend, political art, is everywhere to assist us in our thinking. Look around! The most fun place to start enjoying the Free State of Art is always at the movies. And what better place than the recent HBO offering All The Way, about the 36th president, Lyndon B. Johnson. Inspired by Robert Schenkkan’s play of the same name, the film is set right in the middle of the Civil Rights Movement. Can art get any more political? Maybe Mount Rushmore … but political art doesn’t have to be about United States presidents or Hillary or Trump (or Gary Johnson!).

And what better political art than theater? Because we have the new hit play Hamilton, an American musical that scarfed up 11 Tony awards including Best Musical. So when did history get so interesting? Who knew? And with the current ability to view anything anytime anywhere, there is no excuse for not staying informed or entertained. I am just now getting to the new version of Roots. And I am old enough to remember the enormous impact the first Roots had on the American psyche — when you had to wait a week for the next part. With DVDs you can just take a crash course in House of Cards or Homeland wherever you are. Then there is the Free State of Jones with our very favorite Texan, Matthew McConaughey. And it doesn’t get any better than BrainDead to capture the zeitgeist of our elections. And BrainDead is a true story, too. Boy! And art really got its way with the new image of Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill. Isn’t art great!

Everyday we open our newspapers to the editorial section to find the latest political cartoon. I prefer This Modern World by Tom Tomorrow. Oh Gosh! Lets not leave out The Danish Girl, a timely film about art and artists and changing gender. And don’t forget Myra Breckinridge starring Raquel Welch. Adapted from Gore Vidal’s 1968 novel, it was a very scandalous movie in its day. I highly recommend it — one of my favorite films.

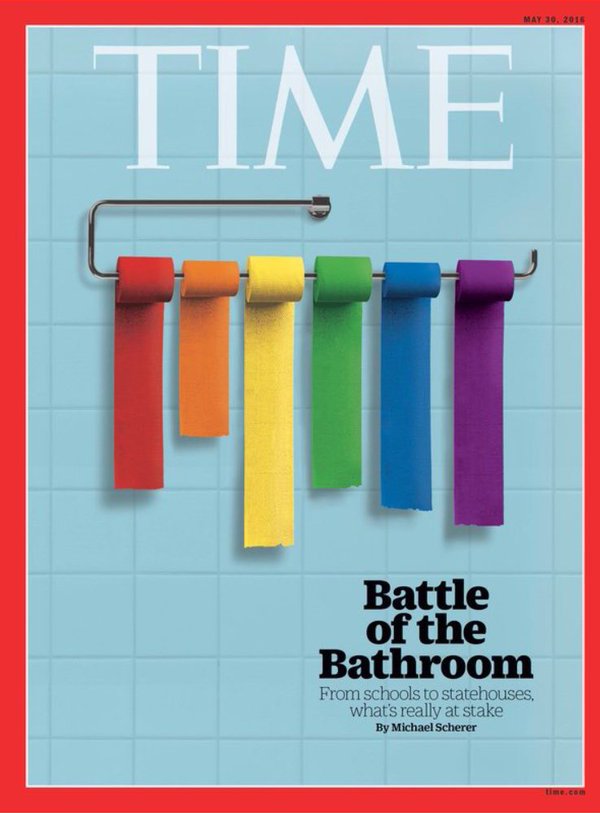

Maybe you saw the recent Time magazine cover with the six rolls of toilet paper in rainbow colors as a comment on the current bathroom politics. Political art on the cover of Time. And toilet paper! The poetry and visual brevity of it says everything, with just two symbols. It reminds me of Ken Little’s art piece Homeland Security — a white picket fence in the shape of the United States. The City of San Antonio should have bought that. And you know what, if the art community learns to be more supportive of political art, we might be a more impressive art scene nationally.

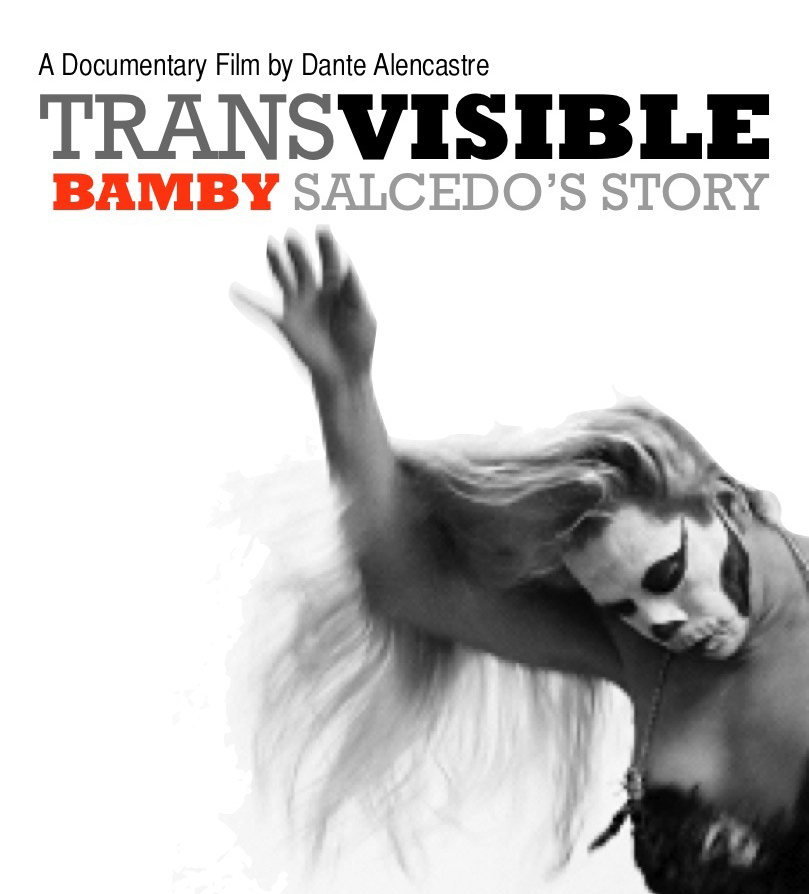

Locally we always have the Esperanza Peace and Justice Center that burns a torch for political art all year-round. Earlier in July, the nonprofit screened the documentary Transvisible: The Bamby Salcedo Story. Founder of the TransLatin@ Coalition, Salcedo attended the San Antonio screening and also led a community organizing workshop.

Of special interest to our growing consciousness are the Shepard Fairey prints on display at the McNay Art Museum. You remember Fairey, the artist who got our attention in 2008 with the Hope poster he designed for Barack Obama’s presidential campaign. Gifted to the McNay by Harriett and Ricardo Romo, the nine Fairey prints offer both political and social messages. I found his use of just four colors (black, white, tan and red) also play a subliminal political role by alluding to skin colors. With titles like Obey 95, Immigration Reform Now, Operation Oil Freedom and Know Your Rights, there is no mistake that a political agenda is afoot with Fairey.

In the words of McNay curator Lyle Williams: “Keenly aware of the art historical canon, Shepard Fairey is very much a part of a great, centuries-old tradition of making prints in the service of social commentary and political protest. Like Honoré Daumier championing the freedom of the press in 19th-century France or the members of Mexico’s Taller de Gráfica Popular fighting the progress of fascism in the 1930s and ’40s, Shepard Fairey and his art are on a mission, a mission to call attention to social and economic injustice and to remind us all of our responsibility to be actively engaged in the political process.”

And our most loyal curator and art commentator David Rubin, who is never at a loss for words, offers: “One of the positive results of political art is that it can stimulate dialogue on relevant topics that most people shy away from discussing. In this respect, I urge everyone to watch the conversation I had recently at Bihl Haus Arts with exhibiting artists Mark Anthony Martinez and Michael Martinez, who use installation and new media formats to investigate racism, homophobia and transphobia. Our discussion could not have been any more timely, in that it took place six days following the great tragedy in Orlando, Florida. A video recording of the talk can be viewed at this link.

Talking with Kathy Vargas is always a treat and, as always, she had a politically minded artist in mind: Vincent Valdez. “About two months ago I saw a great article on Vincent Valdez in The New York Times. The article was about a huge painting he’s doing of the Ku Klux Klan, hooded, in full regalia. The scene is a Klan gathering, but the Klan members are doing typical, everyday things: talking on cell phones, tending children/carrying baby, etc. The message I got from the painting was a revelation: racism is everywhere present among us, and it’s still “hooded.” We don’t always know who the racists are. They’re at the grocery store, it’s the person on the cell phone next to you, or the woman tending her baby. We don’t know who’s who; they’re cloaked. The racist, the homophobe, the misogynist all look like everyone else. In this age of too-quick gun violence that few people seem to want to curb (note the Congressional Democrats sitting-in for gun laws) in a time of political rallying around an “us/them” mentality, it seems that we’ve made it too easy to hate and “other-ize.” Proof of that is the fact that The New York Times was eager to run with a story about a Texas-based artist making political art. Vincent made a great painting about an important topic, and I’m so happy that the nation is aware of it. What’s even more poignant is that the story made it into Texas from the Times. Glasstire picked it up after New York. Along with the story, there was an important question asked: Is the truly great art of our times going to need to be political? Back when I was in grad school, I remember being told not to make political art; that instead, art needed to be “universal” (abstract or minimalist) to be accepted. These days, political art is universal. It’s about time! I am so proud of Vincent Valdez! Thank you, Vincent, for reminding us of what matters.”

A few words from Vincent Valdez: “Hello Gene, thanks for sending this … I am under a very heavy deadline to complete the 45-foot Klan painting this summer for the opening in September and still have a long way to go. Unfortunately, I don’t have the extra time to contribute some writing to your publication. I appreciate your offer. Hope you are well.”

Michael Mehl, the force behind Fotoseptiembre, provided his thoughts on the matter: “Invariably, there’s a lot of posturing that goes on when you mix art and politics, which is why I am always suspicious of the political pronunciations of artists, and of politicians who profess to “support” the arts. A political act is committed by anyone whose actions are driven by a rigorous intellect and principled integrity. This applies to artists as well. However, when purportedly principled artists seek to derive a livelihood from the arts it becomes clear that intellect and integrity are often at odds with the particular circumstances that allow for such a livelihood. Also, there is a tendency to mistake rigor and integrity for blissful stubbornness and uninformed, intractable opinions — which leads to a decidedly narrow understanding of how society actually works … In my book, honesty is the one constant that defines true polity. And it has always been my contention that the only honest artist is one who has a day job … In our 2016 Fotoseptiembre lineup as part of our curated SAFOTO Web Galleries, there are several artists whose work would fall in the political category, even if the artists themselves do not perceive their work as such. One is Chang Chaotang, a photographer/curator from Taipei, Taiwan, who has dedicated decades to both creating and preserving the cultural and historical identity of Taiwan as an independent country. Roger Ballen, from Johannesburg, South Africa, uses a style he calls “documentary fiction” to create metaphors derived from social criticism, while photographing people from the margins of South African society. There is Frank Herfort (Germany/Russia), who creates images that reflect the ironies and absurdities of daily Russian life. There is Damian Borges, a lifelong environmental activist and photographer from Tenerife, in the Canary islands, whose images are personal commentaries on environmental decay. Keith Dannemiller photographs the abstract surrealism of daily street life in Mexico City. And Chas Ray Krider, in his pursuit of a modern noir aesthetic is both celebrated and maligned for his unabashed images of women in various stages of undress. What most don’t understand is that Chas is only a photographic interpreter, creating images based on the specific ideas and fantasies conveyed to him by his subjects. ”

As for Bill FitzGibbons: “I think that one of the most important political artists of our time is Hans Haacke. Hans Haacke was a member of Group Zero in the ’50s and ’60s, an important art movement begun by German artists Otto Piene and Heinz Mack. Group Zero was interested in minimalism and Italian arte povera. In the ’70s and ’80s, his art practice took him to criticizing social and political systems. In “Documenta 7” in 1982, he was critical of President Reagan and Margaret Thatcher and their embracing of nuclear arms. According to Wikepedia, at the 2000 Whitney Biennial, Haacke presented a piece that is a direct reaction to art censorship. The piece called Sanitation featured six anti-art quotes from U.S. political figures on each side of mounted American flags. The quotes were in a Gothic-style script typeface once favored by Hitler’s Third Reich. On the floor was an excerpt of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, guaranteeing freedom of speech and expression.”

Well, I tell you, this political art talk can wear you out. It makes you want to just sit back and listen to Woody Guthrie sing “This Land Is Your Land.” Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born July 14, 1912. He gave birth to the modern protest song and pasted “This Machine Kills Fascists” onto his guitars. The band Anti-Flag used the phrase as a song title.

David Freeman says: “South Texas is a wonderful region to live within the context and concepts of political happenings. We exist within a brilliant and bountiful amount of material for political art, such as the drug cartel and their history of Medieval violence, institutionalized medical and political corruption, greed and the coyotes of sex trafficking and the horrors of immigration … and let’s not forget we are in the top 10 for the scaredest, fattest and stupidest cities in America. All this is beautifully tragic fodder for artworks but it’s a challenging place to try to find an audience receptive and understanding of these issues; they haven’t been born yet. Artists must farm out their work to find an audience for concepts of heavy-handed political ideas, perceptions and thought dealing with process, content and genuine concepts. But it is getting better … in baby steps, an example of a growth spurt is: ‘Un/Provincial: Art of South Texas’ at the Brownsville Museum of Fine Art. A group show mostly dealing with the affairs of our social state of mind — a geo-political and regional visual dialog of South Texas. Candé Aguilar created and generated the idea for this exhibit and it was curated by Jennifer Cahn — contemporary curator for the International Museum of Art and Science. An overview of a few of the more political musing are prints by Jesus De La Rosa of guns, tanks and piñatas that speak of design and war and the harshness of undocumented people’s life-and-death journey seeking a new secure life. Veronica Jaeger depicts the politics of man-made architecture and how it affects the feminine psyche, her uber-realistic portraits of big, vacuous glazed-eyed female heads floating inside constructions of heavy male ideals of geometric marks show a nuclear divide of male and female ideals of social address for women today in art and architecture, especially dealing with politics of environmental consciousness. Mark Clarks stylized paintings of Mesoamerican figures let us imagine what the paintings of Aztecs would be today if they were present and dealing with modern concerns of cartel violence and immigration issues. Mauricio Saenz videos’ depict a conceptual beauty and sophistication that negotiate immigration and colonization issues. Its a strong and beautiful exhibit full of truth and a genuine vision of our collective countenance.”

But we are not finished yet. We still have fashion to follow. And we know that hemlines are not the only political statement. We see how clothing design, colors and words can carry a message loud and clear to any occasion, such as the design choices made by Nancy Reagan or Jackie Kennedy. This is how politicians use clothes to tell the story of their rule. But just as interesting is the street theater of T-shirts with messages or better still, consider the Fashion Institute of Technology – State University of New York Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology’s exhibition “Fashion and Politics.”

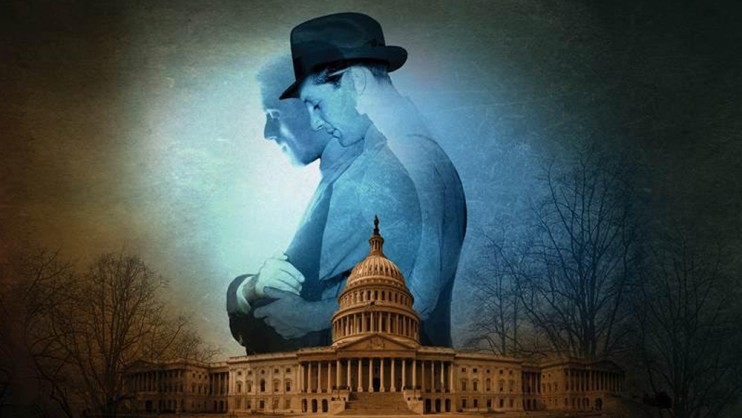

I am afraid we have to go to Cincinnati for a political opera this July. Fellow Travelers is based on the 2007 novel by Thomas Mallon. At the height of the McCarthy era in 1950s Washington, D.C., recent college grad Timothy Laughlin is eager to join the crusade against communism. A chance encounter with handsome State Department official Hawkins Fuller leads to Tim’s first job — and his first love affair with a man. Drawn into a maelstrom of deceit, Tim struggles to reconcile his political convictions and his forbidden love for Fuller — an entanglement that will end in a stunning act of betrayal.

By the way, the book To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee appeared on July 11, 1960. It has been translated into more than 40 languages and sold over 30 million copies. The 1962 movie starring Gregory Peck won three Oscars.

For additional Political Art Month reading, check out the San Antonio Current‘s “Political Art Month Scavenger Hunt: A Survey of the Obvious, Forgotten and Controversial.”